unearthing the past for the future: archaeolgy to combat climate crisis?

ARCHAEOLOGY OF CLIMATE CHANGE

matilda jones

46960511

1, 176 / 1,200

Spoiler alert: climate change is the single biggest threat facing humanity!

If this is news to you, your head must be so deep in the sand that archaeologists may never unearth you.

Climate change refers to “long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns.” These shifts are usually natural, changing in response to solar or volcanic activity; however since the 1800s “climate scientists have showed that humans are responsible for virtually all global heating … primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas.”

This is extremely problematic.

The consequences of climate change are devastating and far reaching. Some environmental impacts include:

- Droughts

- Water scarcity

- Fires

- Rising sea levels

- Storms

- Acidification of oceans

- Degradation of biodiversity

- Increase of natural disasters

Not only are any one of these incredibly destructive, but the severity and frequency of these will only be heightened. Furthermore, all impacts will in turn create an exceedingly difficult environment for humanity to survive. Some consequences directly affecting humanity are as follows:

- Food insecurity

- Water insecurity

- Economic disruption

- Conflict

- Terrorism

- Spread of disease

- Heat stress

So I’m sure it comes as no surprise that climate change threatens humanity’s very existence. Currently as it stands, “the climate emergency is a race we are losing, but it is a race we can win.”

So how can archaeology possibly assist in combatting climate change?

Archaeology is unique in that it offers us the gift of hindsight. Burke, a leading climate archaeologist states that the discipline provides “opportunities to identify the factors that promoted human resilience in the past and apply the knowledge gained to the present, contributing a much-needed, long-term perspective to climate research.” Through the collaboration of archaeological research and climate data, archaeology can aid to develop strategies, methods and processes in responding to the climate crisis; and furthermore, help foster a more harmonious relationship between humans and the earth.

The discipline draws on numerous research methods to inform the present of our past. For example, archaeologists can analyse tree rings (dendroclimatology), sediment cores, seas and lake sediments growth of stalagmites and stalactites, count pollen particles, as well as literary sources for indicators of climate fluctuations and changes. When assessed together, an image of a dynamic and ever-changing climate emerges, one in which humans must also be an active participant of perpetual evolution.

Case Study: The Nile River

The Nile River is the longest in the world (6,600 km) located in northeastern Africa, spanning numerous countries, but most notably (for the purposes of this blog) Egypt.

The Nile was essential to the survival of Egyptian society: “every aspect of life in Egypt depended on the river – the Nile provided food and resources, land for agriculture, a means of travel, and was critical in the transportation of materials for building projects and other large-scale endeavours.” Even the historian Herodotus heralded in its glory, calling Egypt “the gift of the Nile.”

Despite this, the narrative that is often constructed is one where humans operate as “the main agents of history,” rendering the Nile as the “environmental backdrop” to a dynamic civilisation.

However, this could not be further from the truth. By engaging archaeology and climate research, it becomes clear that the driving factor of change, toppling dynasties and driving technological developments is the Nile. Suffice to say, the Nile River was a “sustaining force in the development of the culture and state of ancient Egypt.”

Thus, any fluctuations in the Nile’s posed a detrimental threat to ancient Egyptian society.

The North African climate dictated Egypt’s environment and subsequently the Nile. Fluctuations in this climate were directly responsible for the alterations in the Nile’s landscape, raising and lowering flood banks, unearthing and sinking islands, and modifying the delta. The repercussions of this led to the “rise and fall of proximal settlements.”

The Instructions of Ani illustrate this perfectly:

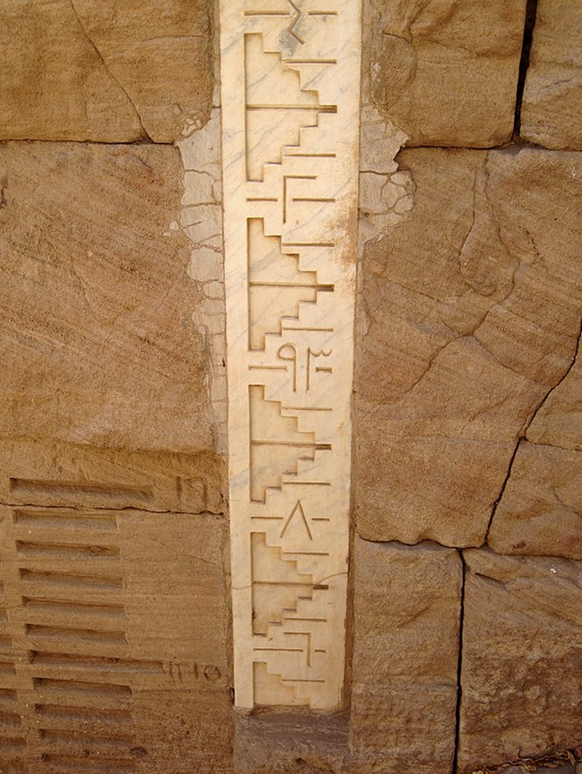

INSTRUCTION OF ANI

When last year’s watercourse is gone, \ Another river is here today; \ Great lakes become dry places, \ Sandbanks turn into depths. \ Man does not have a single way, \ The lord of life confounds him.

In summary, the Nile floodwaters served to “fill the storerooms and enlarge the granaries,” anomalous flood levels could catastrophically impact cultivation. In response, the Ancient Egyptians had to alter their behaviour to adapt to a changing climate.

Nilometers, graduated pillars or etched vertical surfaces were constructed, to record the height of the Nile during its annual floods. In recording the flood heights, Egyptians were able to predict or forecast riverine behaviour, and prepare accordingly. Thus the practice can be observed to be “a dialogue between its people and its landscape.”

You might even infer that the ancient Egyptians noticed that climatic change was affecting their daily operations and sought to alter their behaviour so that repercussions were not felt (hint hint twenty first century).

Analysis of the Discipline: Archaeology of Climate Change

The archaeology of Climate Change proves to be extremely exciting discipline in shaping responses to our current climate crisis, however, scrutiny of the available research must be conducted. The research published provides the opportunity to view the long-term perspective of climate change as well as the many behavioural responses humans have given which places an emphasis on including traditional ecological knowledge, that is actively platforming Indigenous voices to better understand how to live in partnership with the environment: “there is no route to a safe climate that does not include recognition … and putting into practice Indigenous knowledge and land management.”

However, it must be acknowledged that with any new disciple, there is only a limited amount of data available which unfortunately limits the application of much archaeological research to the current climate crisis. Furthermore, the research is subject to interpretation challenges, and has not gathered the awareness of other archaeological disciplines. This further affects its ability to

aid the climate emergency as without awareness of the research, it cannot be utilised. Finally, our climate emergency requires immediate action – archaeology is not a discipline that operates under narrow time constraints, rather it is a lengthy and time-consuming process.

In weighing up archaeology’s potential application to the climate crisis two statements can be made: that the research is incredibly important and vital, but more research and awareness must be generated.

In conclusion, the overwhelming connection that we can make is that when the earth’s climate changes, humans must act. However, unlike today’s society, our ancestors recognised that they must learn and address their behaviour so that future generations aka us, are not deprived of earth’s resources. It’s time to take a page out of their book, or papyrus, or scroll, etc; we need to collaborate with all disciplines and help restore our earth.

“We are only doomed if we are unwilling to listen to the past.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amanda Logan. (2013). Cha(lle)nging Our Questions: Toward an Archaeology of Food Security. SAA Archaeological Record, 20–23.

Charlotta Hillerdal & Kate Britton. (n.d.). Archaeologies of Climate Change. Université Laval, 43, 265–288.

Christine L Johnston. (2020). Conclusion: Towards a ‘GeoEgyptology.’ Tucson: University of Arizona Egyptian Expedition, 217–272.

Climate change. (n.d.). World Health Organisation.

Climate change: a threat to human wellbeing and health of the plan (pp. 1–5). (2022). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

David Vetter. (2021). How Archaeology Could Help Deal With A New, Old Enemy: Climate Change. Forbes.

Egypt and the Nile. (n.d.). Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Felix Höflmayer. (2017). The Late Third Millennium in the Ancient Near East: Chronology, C14 and Climate Change. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Katherine Blouin. (2021). How the climate crisis and its repair are rooted in ancient (hi)stories. Everyday Orientalism.

Luke Kemp. (2019). Are we on the road to civilisation collapse? BBC.

Mary Rockman & Carrie Hritz. (2020). Expanding use of archaeology in climate change response by changing its social environment. PNAS.

Michael Le Page. (2012). Five civilisations that climate change may have doomed. New Scientist.

Michael Marshall. (2012). Climate change: The great civilisation destroyer? New Scientist.

The Climate Crisis – A Race We Can Win. (n.d.). United Nations.

Thomas Schneider & Christine L. Johnston. (2021). The Gift of the Nile? Ancient Egypt and the Environment. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections.

Using archeology to better understand climate change. (2021). University of Montreal.

What Is Climate Change? (n.d.). United Nations.

Yale Nile Initiative. (n.d.). Yale Nile Initiative.

FURTHER READING

Paul Brown. (2022). What archaeologists discovered about climate change in prehistoric England. The Guardian.

Ariane Burke, Matthew C Peros B, Colin D Wren, & Francesco S R Pausata. (2021). The archaeology of climate change: The case for cultural diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(30), 1–10.

Kino Lorber. (2019). Anthropocene.

Climate Change. (2019). National Park Service.

Self reflection

What do you like best about your blog?

I believe my blog is strengthened by my exploration of different notions surrounding the archaeology of climate change. I also love how much research I was able to draw upon. I believe that the great variety of sources provided significant depth and authority to my blog post.

What do you like least about your blog?

I believe I was too general overall and should have narrowed my approach to provide further details on various specifics. In particular, I feel as if I should have included a variety case studies to demonstrate how important the discipline is.

What would you modify if you had an extra 24 hours to spend on your blog?

I would rectify the above answer and provide more examples of how humans have adapted to periods of climate change throughout history. I would also loved to have touched on some practices contemporary society can adopt, practices developed by Indigenous persons worldwide. I would also attempt to cut down on a general overview of climate change archeology and provide greater analysis of the current research available.

Self reflection